Joe Meno

Once we aped a couple fighting on the bus. Mary pretended to be the girl and I aped the guy. The girl was wiping her wet eyes and saying, “No, I don’t believe you. No,” and so Mary repeated the same thing. They didn’t notice us. The guy said, “What do I have to do? What do I have to do to get you to believe me?” and so I asked the same thing. We made faces at each other like people who were people trying to stay in love. It took a while for the couple to actually figure out what we were doing. When they saw the scene we were making, the guy grabbed me by the front of my shirt. He started yelling. “What the fuck are you doing? What the fuck are you doing?” I went limp, but Mary kept on going. “What the fuck are you doing? What the fuck are you doing?” she shouted, grabbing onto my shirt, too. The guy turned to her and pushed her and she fell down but by then the bus driver had stopped the bus and we ran off, stumbling into the night air, laughing.

—from

“Apes”

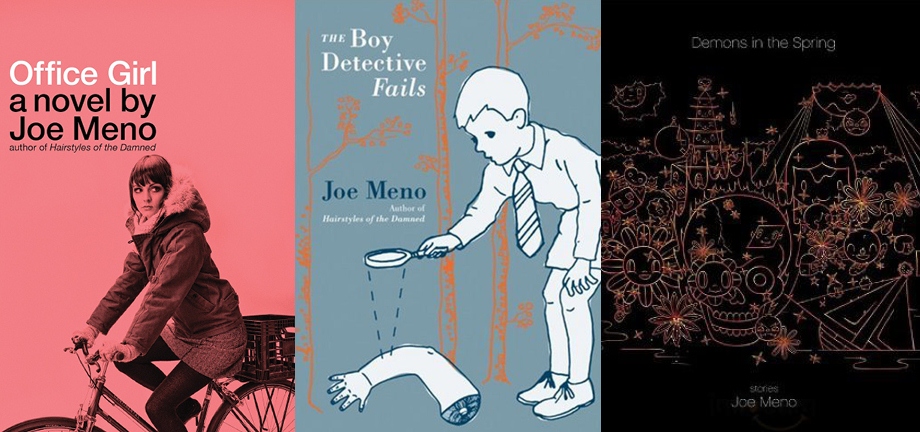

Joe Meno is a fiction writer and playwright living in Chicago. He is the author of six novels, including The Great Perhaps and the just-released Office Girl, and two short story collections, including Demons in the Spring. His short fiction has been published in journals like McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, One Story, Swink, LIT, TriQuarterly, Other Voices and Gulf Coast, and has been broadcast on NPR. He was a contributing editor to Punk Planet, the seminal underground arts and politics magazine. His story “Apes” appears in Unstuck #1.

Interview by Allie Werner

UNSTUCK: Way back in 2005, you gave an interview to Bookslut in which you discussed your belief that independent publishers were going to start majorly outshining and outmaneuvering the big publishing houses. Now that we're here in the future, do you feel like that's already happening? What do you find most exciting about independent publishing today?

JOE MENO: I still feel pretty strongly that small, independent publishers are a lot more willing to take risks in both content and form. If you look at the kinds of books Grove Press or McSweeney's or Akashic put out, there's a distinct feeling of daring.

I feel

like Office Girl [Meno's latest

novel] is daring in how

slight and how quiet it is, and

how pretty normal the characters are. That, believe it

or not, doesn't fit in with what

most contemporary literary publishers are

putting out.

Most

contemporary novels are really interested in

telling these epic stories, or

dealing with contemporary events. Novels

have become a lot more about

information and how the world works than

about people and how they relate to

other people.

The fact that Akashic let me work with two great artists is also pretty bold. I've experimented with the relationship between the text and the actual layout in other books like Demons in the Spring and The Boy Detective Fails, which were both books Akashic published. They have a willingness to allow the writer to follow his curiosity. I've had these long conversations with Johnny Temple, the publisher, about what a book can do in the 21st century that other media can't.

UNSTUCK: I'd like to talk a little bit more about the drawings and photography in Office Girl, and your work with Cody Hudson and Todd Baxter. How did the collaboration with these other artists work?

JOE MENO: They're both good pals of mine. I finished a draft of the book and realized how central art was to the story and asked what ideas they might have, Cody immediately suggested certain ideas, then Todd suggested others, and we all began to agree that the artwork should reflect the tone of the book. We decided pretty quickly on small black-and-white drawings, to reference Odile's graffiti, and black-and-white snapshot photos. We wanted to create a sense of intimacy and also to connect to the zine tradition which is referenced in the book. Basically, make a book that was a zine or a kind of Jean-Luc Godard movie in book form. Again, that's pretty risky for a publisher to put out there.

UNSTUCK: Yeah—as I was reading the book, I often felt like I was reading a very long zine. Not just in regard to the multimedia content, but also to the choice of font, typesetting, and the actual physical size of the book.

JOE MENO:

Cody

and I looked at a

lot of different fonts, experimented with different

sizes,

colors. We wanted the actual

physical shape, the font, to reflect what the book

was about.

Which was

these brief moments that occur and then

disappear. And how we spend a lot of

time trying to capture those

moments. Which is basically writing. Or any kind of art. So we

wanted all the

design

elements to have this small, temporary quality. Again,

other

publishers I've worked with do

not want to have these kinds of conversations. They want to hand

you

a cover and say,

"this is your book."

UNSTUCK: I was wondering how much control you had as an author over the design of the book, because the physical design reflects its content so well. And it seems like you had quite a bit of input!

JOE MENO: That's one of the great advantages working with a smaller, independent publisher. For someone like me, who's looking at the relationship between form and content, it's a huge deal. I believe books, if they're to continue in printed form, have to offer an experience you can't get anywhere else. They have to be intimate. They have to be art objects. It was Cody's idea to add the actual zine insert into the book. Which, again, seems something so uniquely connected to the story and what a book can do.

UNSTUCK: I liked how the pages actually changed color to indicate the zine insert. It did make it seem like an external object had been stapled into the middle of this novel.

JOE MENO: Again, we were trying to find ways to make the experience of reading the book unlike other narrative experiences in film, television, or theatre.

UNSTUCK: It was strange for me to read a new book set in the late 90s, because I was born in '88 and the 90s are the first decade I have any memory of. What made you decide to set Office Girl in this particular time period?

JOE MENO: There're a few reasons it's set in 1999. I was in my mid-twenties in 1999, which is roughly the same age as the two main characters. There was something about the particular historical and cultural moment as well, where it felt like the entire planet was waiting for something important to happen—the end of the millennium, the end of Bill Clinton’s presidency, the end of the world—but that also felt oddly insular or safe. I feel lucky to have become a young adult in the 90s because there was nothing to worry about but art and music. Also, I have no idea how young people fall in love in the twenty-first century. There's all this technology now. I just wanted to focus on the characters.

UNSTUCK: It's interesting that you mention technology, because it really stood out to me that neither Odile nor Jack seemed to have a home computer.

JOE MENO: I didn't in 1999. I had this Radio Shack word processor that had one program on it. Though Jack is pretty contemporary in a lot of the ways he moves about the world. He constantly documents the world around him using his tape player. It's pretty much the same as texting or Facebook. It's digital graffiti.

UNSTUCK:

Exactly. The

relationship

between the characters, their situations, and their mannerisms

all

felt very

contemporary to me, which is why differences in the forms

of

technology and documentation are

what made me go, "This is a sort of

period piece."

JOE MENO: Yeah, like I said, I was twenty-five in ‘99 and it usually takes me ten years or so to write about what was happening to me.

UNSTUCK: I noticed you included a list of theme music in the back pages of Office Girl, and I really liked that little addendum. Do you often listen to music as you write? Do you find that music informs your writing, or does what you're writing reflect your music choices?

JOE MENO: I can't listen to music while I'm actually writing. But I try to capture some of the same tone or mood from a group of artists. I've done this for all the novels I've written. I try to identify the sound, the mood of the book through music and then translate it to words. It's like taking something abstract and trying to give some kind of form. Cody Hudson and I actually sent some songs back and forth as we were figuring out the design elements.

UNSTUCK: So how did Office Girl originate?

JOE MENO: It started as a short story, then it was a play, and then I wrote it as a novel. I've done this for a number of my other novels. Writing it as a short story helps me get it down. Writing it as a play helps me figure out the characters and scenes. And then when I develop it as a novel, I'm looking at the relationship between form and content.

UNSTUCK: "Apes," the story of yours that appears in the debut issue of Unstuck, seems to address some of the same art and performance issues that Office Girl does. Gorilla/guerilla art.

JOE MENO: Ha! Gorilla/guerilla. I never thought of that. Over the last three years, I wrote about five or six stories about young people, people in their twenties. In some way, they all had something to do with art and sex. This is usually when I realize, “Oh, this is all probably going to end up as a novel.” So “Apes” was one of those. It definitely has a darker feel than Office Girl and some of the other young "art school people in love" pieces I wrote. But the idea of two people doing these public exercises, and how that affects their relationship, is pretty consistent with the book. To be honest, I'm really proud of the ending of “Apes.” I have no idea why.

UNSTUCK: It’s a bit of a surreal moment, but in a way it feels natural and plausible.

JOE MENO: I really like that he goes off with the weird, Christian girl. I feel like I know a lot of people like that. People are desperately looking for someone, anyone, a little stronger, a little more ambitious than them. It's how the punk kids I used to know all became Born-Again. They went from one dogma to another.

UNSTUCK: Yes, there's this interesting, almost invisible power struggle going on between Mary and the Christian girl on the bus. Where the girl is being mocked, but she's trying to avoid being hurt.

JOE MENO: Yeah, the Christian girl wins. Because she's nicer. There's no meaning behind that, other than the narrator is kind of weak and knows at some point Mary is going to be through with him.

The soundtrack for that story would be This Bike is a Pipebomb's "Mouseteeth."

UNSTUCK:

In

"Apes," the two main

characters spend most of their free time

imitating other people. A good portion of

the aping sessions in this story seem

to take place on public transit. Why do you

think public transit works so well

as a setting in short fiction? What's the

strangest encounter you've had while

riding the bus?

JOE MENO:

That's

a good question.

Short fiction is all about compression. Compression of time,

event, dramatic arc. And most

important of all, the use of opposites. So public places

work

well, because there

are usually lots of different kinds of people forced up

beside

each other.

There's

Flannery O'Connor's majestic bus story

“Everything That Rises Must Converge.”

As for the last part of the question, I don't take the bus. I take the subway. For some reason, at least in Chicago, there's a very different atmosphere on the El. The bus—and this is terrible to admit—is way more like a doctor's waiting room. There is a sense of frustration, confusion, disappointment, and rage. Most people who ride the bus are not doing it because they want to, which lends it the place to be particularly dramatic.

UNSTUCK: Office Girl, meanwhile, features a lot of bicycles. So, bikes versus public transit. Which is the superior form of literary transportation?

JOE MENO: For a sad story about ruined people, the bus. For a love story, bicycles.

UNSTUCK: What are you reading right now?

JOE MENO: Stanley Elkin's Criers and Kibbitzers, Kibbitzers and Criers. It's a short story collection. He was this major post-modern, extremely imaginative powerhouse. He won the National Book Critics Circle prize twice and he's all but forgotten now. He's really a progenitor of what you guys are doing in Unstuck.

* * *

Allie Werner is a graduate of Reed College. Before joining Unstuck as an Assistant Editor, she read slush for Tin House and interned with American Short Fiction. Her first published story appeared in Storyglossia last summer. She can be found online at A. is A. In her spare time she enjoys coffee and comic books, preferably simultaneously.